Cradle to Cradle…Twenty Years Later

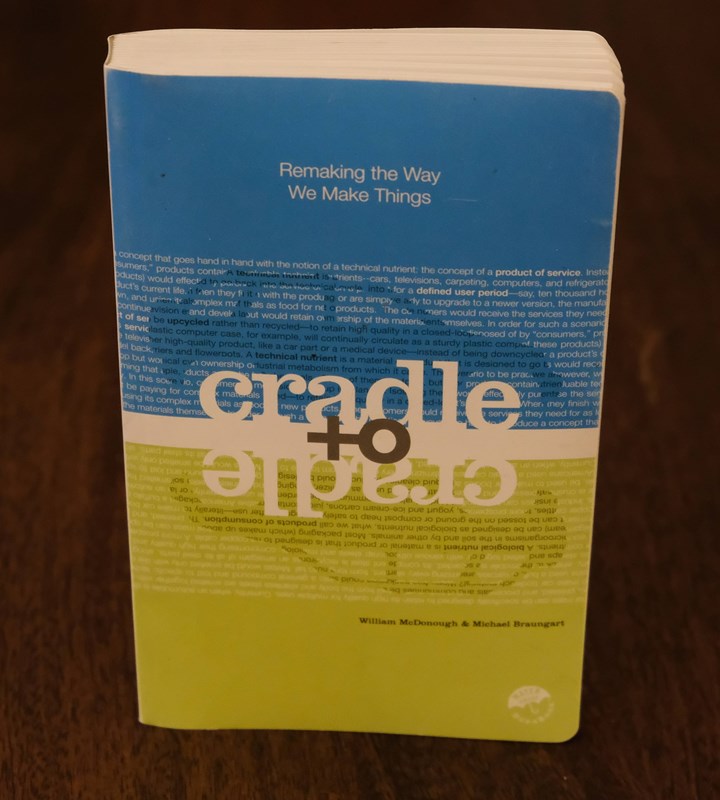

My introduction to the concept of a circular economy came from Cradle to Cradle, a 2002 book by chemist Michael Braungart and architect William McDonough.

Cradle to Cradle (2002) by Braungart and McDonough. The author’s own copy has held up well.

The book itself was a singular object, printed on recyclable plastic with nontoxic ink. The ideas within seemed revolutionary. I studied mechanical engineering, but sustainability, as far as I knew, was about energy efficiency and alternative energy technologies. No one I knew was talking about designing for the end of a product’s lifecycle. There was design for manufacturability, usability, reliability, maintenance, production capability, and so on. Many of us carried an unspoken assumption that what the user did with a product when they were done with it was of little consequence.

Braungart & McDonough drew on nature as inspiration for their view of a circular process. I will never forget the powerful analogy they used, that of a cherry tree. At first glance, a cherry tree may appear to be an extremely inefficient manufacturing process. Very little of what it produces makes it to the mature product stage, i.e., a new cherry tree. Over the lifespan of the “facility” thousands of “waste” cherries litter the surrounding area.

But they look closer. And we see that cherries become food for birds, for insects, for microorganisms, for humans. The valuable nutrients incorporated by the tree into its fruit carry on and continue to be useful to the entire system, supporting other life, replenishing the soil. The same will happen to the tree itself when it dies and is broken down by fungi. The tree can never make too many cherries because what it is making is inherently useful to the entire system and everything around it.

Over millions of years these organisms have coevolved to create beautiful relationships of making, using, and passing on complex molecules. Nothing in a naturally occurring ecosystem piles up in a heap, not for long.

The organisms with which we share our earth have not yet developed a system for the strange new things we make. Maybe another 10 million years would bring forth a wondrous biological system for processing waste products like used cell phones, bubble wrap, and coffee lids. We don’t have 10 million years.

Braungart & McDounagh describe manufacturing processes built on “technical nutrients” drawing parallels between manufacturing and nature, where contrasting qualities seem so obvious. Many of the materials we have way too much of in all the wrong places, plastics among them, are technical nutrients from this point of view.

Thoughtless disposal of goods at the end of their lifecycle does not only discount the enormous value of the places into which they are disposed. It also discounts the value of the materials, and all of the energy, ingenuity, and hard work that went into extracting, processing, and assembling them.

Increasingly, these “technical nutrients” are becoming a sought-after commodity. Plans are being made to recover them, handle them carefully, and input back into processes to create something new. This trend may have taken a long time to get started, but everywhere we look we see momentum building.

The technical challenges of recycling plastics, along with their ubiquity, durability, and high visibility, have placed them at the center of this flurry of activity. It’s an exciting time to be watching the industry.

Leave a Reply