50 Years of Headlines … Almost

An early “scoop” of mine was a 1975 report on the first use of a microprocessor in plastics machinery controls—for, of all things, a filament winder for composites.

As I approach my 50th anniversary with this magazine in a couple of months, I may be permitted to indulge in some some reminiscences. When I think back on that stretch of time, one of the things that stands out for me is some of the technical trends and innovations that I had the privilege of reporting as they emerged. Here’s a baker’s dozen examples:

• The “unforgettable” plastic: In 1981, a press release landed on my desk announcing the commercialization of a new plastic called “PEEK” (short for polyetheretherketone). A name like that has got to stick in your mind. First reaction: What a cute name! Second reaction: What a heck of an engineering material! In the 1980s and ’90s I attended the public launches of several other new materials—DuPont’s Rynite PET, Eastman’s PETG, Shell’s Carilon polyketone, and Dow’s mLLDPE. I also recall being introduced to the wonders of thermoplastic elastomers, courtesy of Uniroyal’s TPR and Monsanto’s Santoprene (both TPVs).

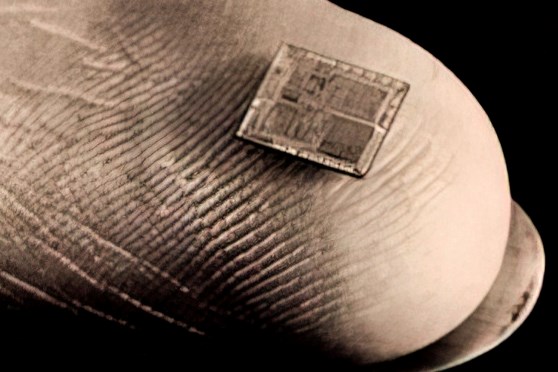

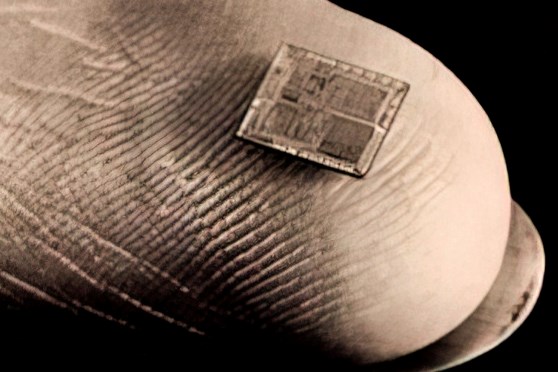

• The first microprocessor in plastics: I traveled to Wisconsin in the fall of 1975 to see this new development in electronics, a subject I knew nothing about, for controlling plastics machinery. This tiny chip that fitted in the palm of your hand could replace a whole cabinet full of wires and cables. It had a name that kind of made sense: a microprocessor. It sounded so smart that it would probably catch on. By 1980 every maker of plastics controls was proclaiming they had a microprocessor! Guess what sort of plastics equipment it was first used on? A filament winder for fiberglass composites.

• Debut of all-electric injection machines: I missed the actual debut back in the 1960s, when Battenfeld floated the idea, but it didn’t take. The time was right, however, in 1984, when I was lucky to make my first visit to a Japanese plastics fair. And there they were: commercial all-electric injection presses from Nissei and prototypes from Niigata. They were only 5 and 10 tons, but I’ve seen very few ideas in plastics picked up so widely and enthusiastically in such a short time.

• Multilayer barrier blow molding: Another case of being at the right trade show at the right time. Interplas ’77 in Birmingham, England—my very first foreign show. Comec and Montedison of Italy jointly introduced barrier bottles made on Comec’s coex blow molder with Montedison’s new EVOH material sandwiched between PP layers. I recall it took a bit of explanation for me to grasp the whole picture, including why a “barrier” bottle was important.

• Gravimetric extrusion control: Back in the 1980s, this one also took a bit of explanation before I “got it.” I was familiar with extrusion gauging and control systems that enabled fine-tuning of the smallest profile variations across a flat web or around the circumference of a pipe, tube, or film bubble. But what’s this about longer-wave adjustment of average product thickness—or weight—in the machine direction?

My first exposure to biopolymers produced by fermentation of plant sugars came from experts on the subject—at Coors Brewing Co. (Photo: RTP Co.)

• Plastics made by “bugs”: I was first introduced to biopolymers—biologically produced by microbial fermentation—by representatives of Coors Brewing Co. back in the early 1980s. Grain could be fermented into not just beverages, but also plastics! Who knew? The Coors exploration of this technology petered out soon, but I was reintroduced to the subject by ICI in England, whose aptly named Biopol resin ended up with the late lamented Metabolix. And of course, Cargill and Dow entered the market with PLA. Their venture became NatureWorks.

• Mold-filling simulation: Originally it was called mold analysis, or just Moldflow, the name of the Australian academic spinoff venture that did the most to popularize the concept. Moldflow was launched in 1978, but I dug into it and wrote the first feature-length article about it in this magazine in 1984. I followed the development of the technology eagerly thereafter—other editors were satisfied to leave this “techy” topic in my hands for at least the next decade.

• Color-matching computers: Another topic that became my baby by default (no one else was eager to delve into it). I wrote the first major article on the subject for this magazine in 1974. Back then, the instruments were desk-sized behemoths that housed what was called a “minicomputer.” The first hand-held spectrophotometers appeared a decade later.

• Two-platen injection presses: I had the concept of these space-saving clamps explained to me for the first time by Italtech in Italy in the 1980s. Made sense for large, bulky presses. Now, of course, they’re used everywhere and for all sizes of machines.

• People-friendly robots: Remember Baxter, the “friendly” robot with a cartoon face on a screen? That was the first time I heard the term “collaborative robot” – now shortened to “cobot.” It was only 2012, but it seems like an age ago. Nowadays, molders are welcoming cobots—even without a face—to soften the impact of ever more acute labor shortages.

• Stretch-blow molding: Anyone remember the Phillips Orbet process or the Beloit Bi-Axomat machine? Anyone? In the 1970s, they were my first exposure to stretch-blow molding, which started back then with an extruded tube, not a molded preform, of polypropylene. Shortly after came the epoch-making PET bottle, championed by DuPont. It was impressed on my consciousness when I wrote up the Cincinnati Milacron ISBM machine, the first one built in the U.S.

• RIM, RRIM, SRIM, etc.: Cincinnati Milacron (now just Milacron, though it’s still in Cincinnati) was also my introduction to reaction injection molding, or RIM. In 1976, I covered Milacron’s introduction of one of the first complete machinery systems for this new polyurethane process. It was used to produce elastomeric exterior panels for 1977 cars, including GM’s Pontiac. RIM soon proliferated into glass-reinforced RRIM and long-fiber “structural” SRIM, and was followed by nylon RIM and DCPD (“Telene”) RIM.

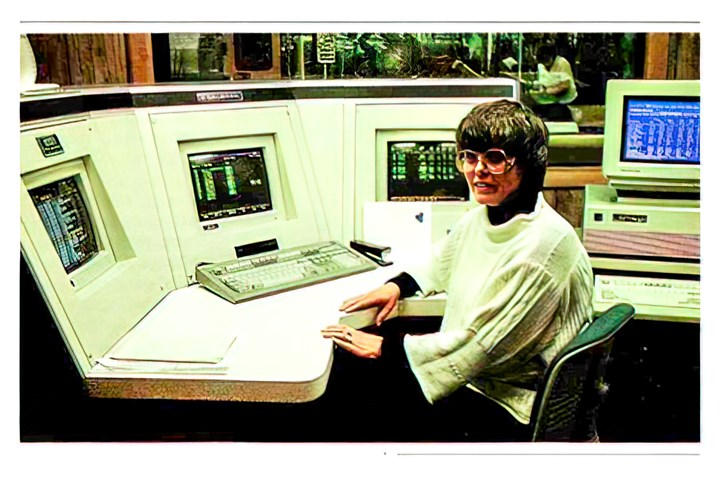

Plastics Technology was onto the scent of Industry 4.0 “smart factories” as early as 1986, when it was called computer-integrated manufacturing, or CIM. This photo was from a 1990 story I did on CIM in blow molding. (Photo: Plastics Technology)

• “Smart manufacturing”: If you’ve stuck with me this far, I’ll end with one of the biggest and most far-reaching trends that is grabbing a lot of headlines today—Industry 4.0, also variously known as the Industrial Internet of Things (IIOT), digitalization, or the coming era of “smart factories.” I’m pleased to say that Plastics Technology caught on to this trend way back before it became fashionable—in the 1980s, in fact. We began pounding the drum editorially for what was then called “computer-integrated manufacturing,” or CIM. We began an annual CIM Leaders Awards competition in 1986, which ran through 1998. By then we got the feeling that CIM had lost its sense of novelty. Fast-forward to the K 2016 show in Düsseldorf, when CIM re-emerged as a prominent industry theme—this time under the moniker “Industry 4.0.” It has been nearly inescapable since then.

By the way, if you want to learn more about the history of many of these developments, look up our “50 Ideas that Changed Plastics,” published in October 2005 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Plastics Technology magazine.

Leave a Reply